Where were you born and where do you reside now?

I was born and raised in Kerala and I am now based in London.

After college you worked as a jewelry designer, becoming the creative head of a jewelry brand in India. How did you make the transition into photography?

It actually happened quite naturally. During my final year of design undergrad, I was interning with jewelry brands and in many Indian companies interns are expected to do a bit of everything. Alongside designing, I started shooting content for their social media. Over time, I realised I was enjoying photography much more than sitting and sketching all day.

That gradually led to a role where I was offered the position of creative head. I was overseeing design, planning campaigns, and also shooting them. The work started getting noticed, and more opportunities came my way within the industry. I began on the commercial photography side and after doing that for a few years, I felt the need to make a complete shift into photography. It didn’t feel like a sudden leap, more like one thing slowly growing into another.

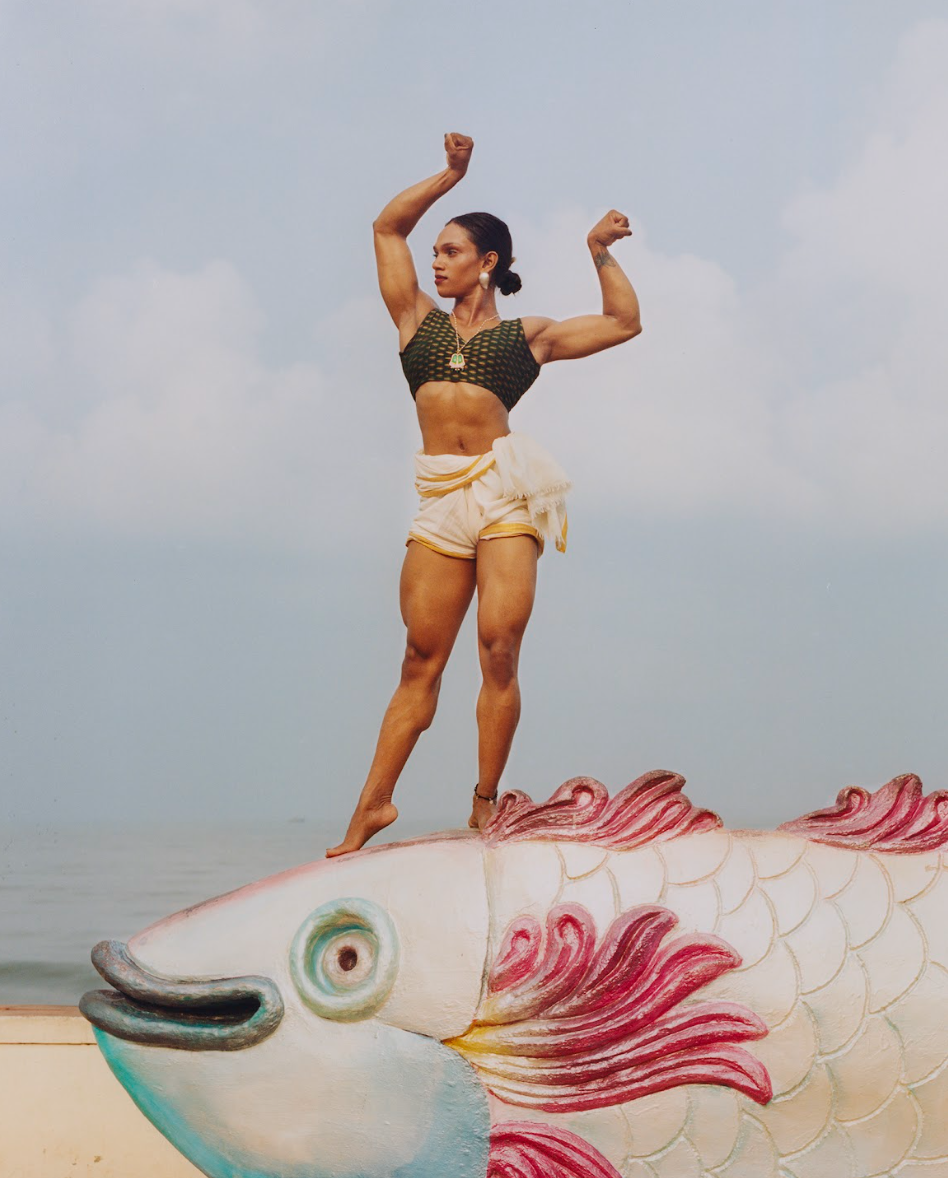

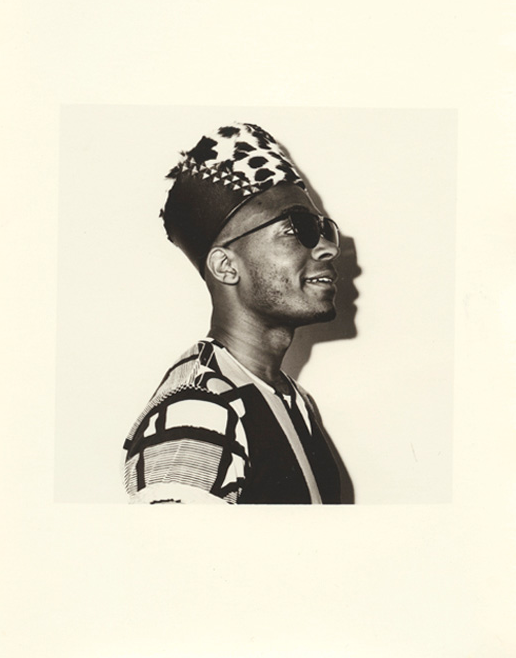

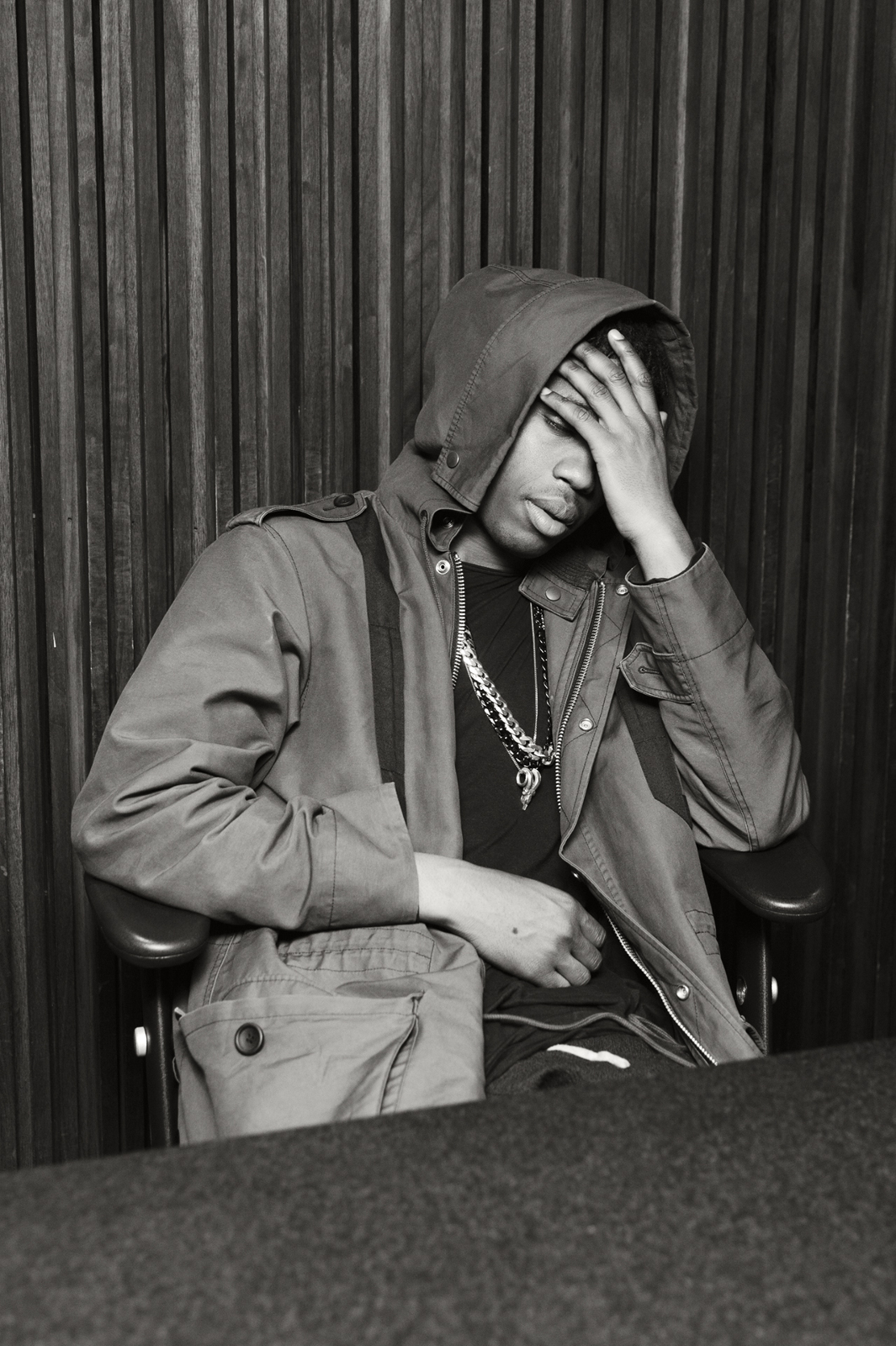

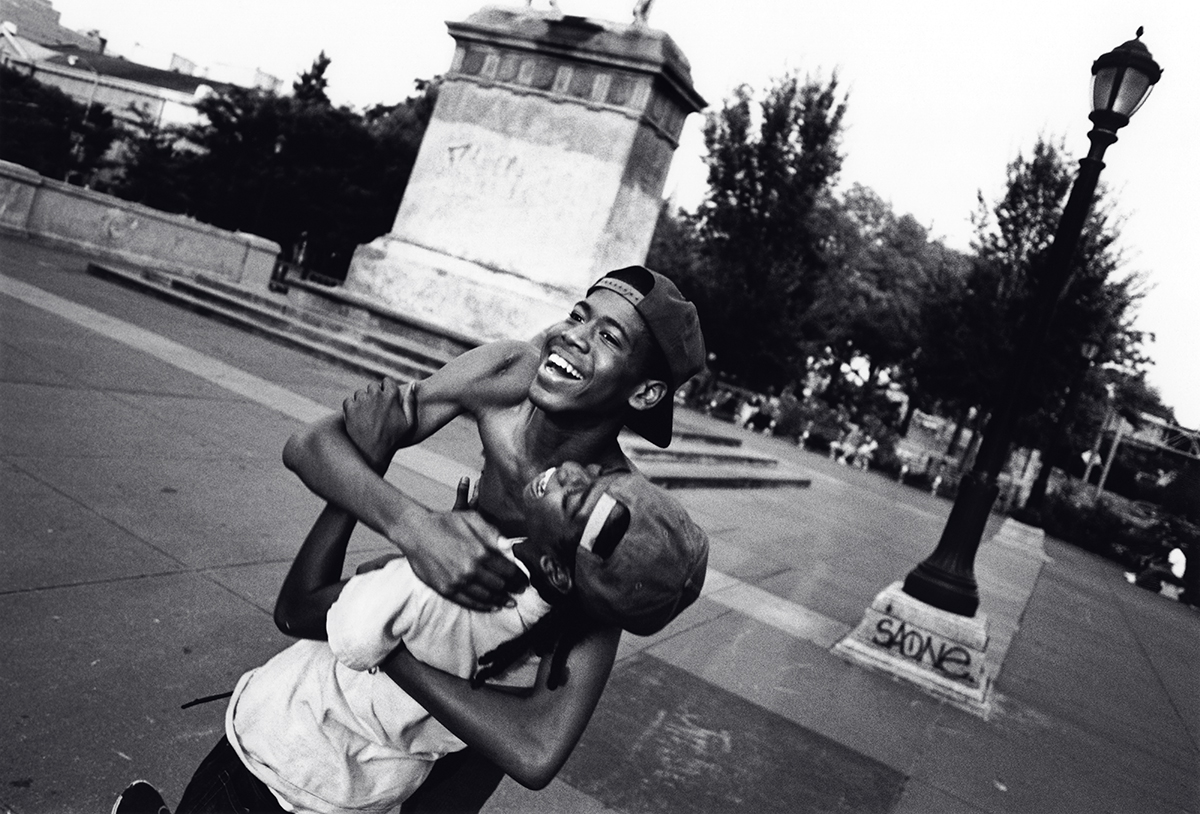

As a child of Indian parents, I understand the taboos and pressures that exist within Indian society. It's refreshing to see your work, offering a new lens through which people can see other aspects of India. Your series on female bodybuilders, Not What You Saw, is a powerful example of this, challenging expectations. How did this series evolve?

I’m really glad you asked this. The pressure to choose a “safe” and socially acceptable career is something many of us grow up with, especially if you come from a middle class or lower middle class family. I think a lot of that pressure comes from the experiences our parents carried. Their struggles, their fears, and their hope that their children will have an easier life than they did.

That weight often falls harder on women. I’ve seen friends and even family who were afraid to dream too big because it felt wrong or out of place. Growing up in Kerala, I witnessed this kind of expectation very closely.

When I first came across female bodybuilders from the region, something immediately clicked. I felt I could understand, at least in part, the resistance and questioning they must have faced. After spending time with them and hearing their stories, I felt a strong need to share their experiences through my work. These weren’t just stories about bodybuilding. They were about choices and persistence.

For me, Not What You Saw became a way to challenge how we look at women and what we think they’re allowed to be. Their victories felt deeply personal to me, beyond the context of sport. It felt like a shared win for anyone who has ever had to push against expectations just to be themselves.

I read that your series Aval (Her), was a healing process for you as you navigated growing up as a queer woman in India. How did that journey shape the themes you choose to explore?

Having cast your subjects for Aval through instagram I am curious to know how social media has played a role in your work, if any?

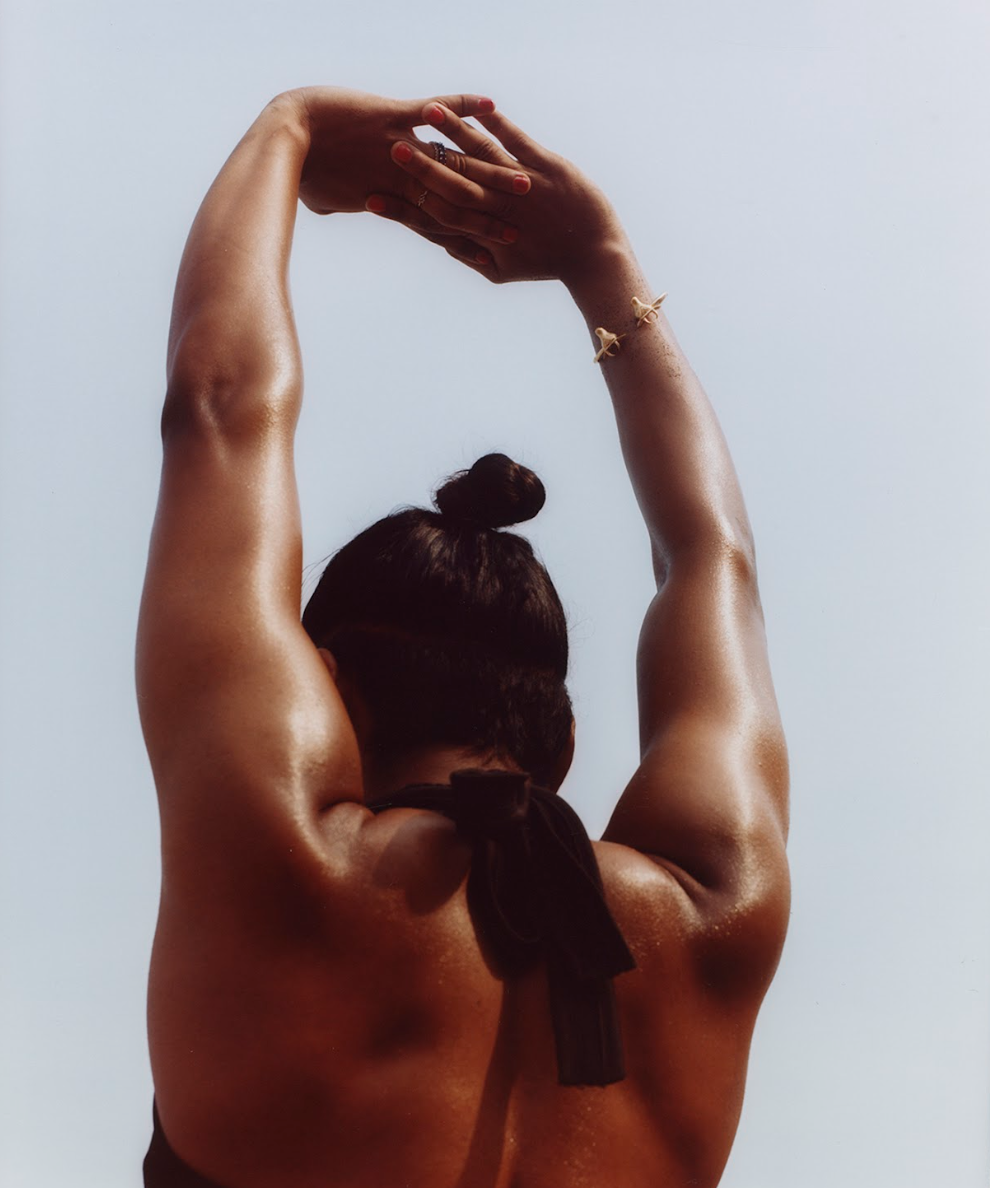

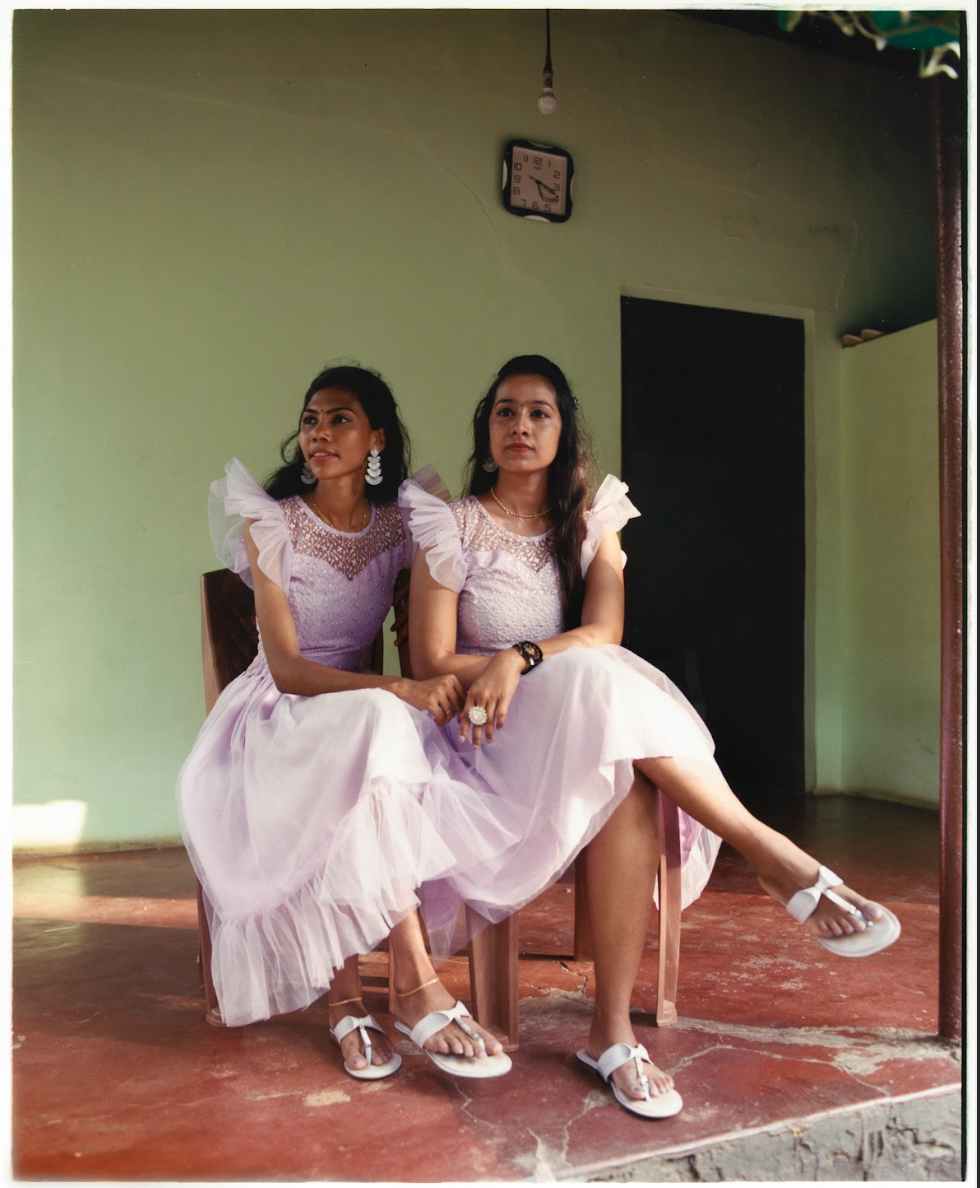

When I began working on Aval, it was the first time I allowed myself to explore themes that felt deeply personal. There was a sense of relief in seeing stories that I could finally relate to, especially because they were so different from the narratives I grew up with.

Growing up, my visual world was shaped almost entirely by Malayalam cinema. I didn’t have much exposure to art films, magazines, or alternative representations of womanhood. A lot of what I saw on screen normalized misogyny, male heroes who were celebrated despite violent behavior, women written as submissive, and female desire often framed as something vulgar or shameful. Looking back, those stories left very little room for young women to understand their bodies, emotions, or sexuality with curiosity or care.

There was also a complete absence of sexual education. Expressing attraction and even basic emotional change during adolescence came with judgment. Those experiences stayed with me for a long time, largely unspoken. Aval became a way to finally give form to those memories, to reflect on them, question them, and gently push back against what I had been taught to accept.

Social media has played an important role in that process. Through Instagram, I was able to connect with people who resonated with the work and were willing to share their own stories. Many of those conversations shaped the project in ways I couldn’t have planned. It also became a space where I could learn from others, people from similar backgrounds, as well as those with very different experiences and see how we are all, in our own ways, trying to unlearn.

Through your composition. lighting, rich color palette, and choice of subjects, your work carries a sense of effortlessness- something incredibly difficult to achieve. What does your process look like when presented with a project? I imagine it shifts between personal and commercial.

Thank you, that means a lot. And yes, the process does shift quite a bit between personal and commercial work.

In commercial projects, the work is ultimately in service to the client. There’s usually a need to be very clear and literal about what the final outcome will look like, sometimes even before the shoot begins. Recently, with the rise of AI, I’ve also started seeing briefs that include AI generated visuals, which adds another layer to navigate. How much room there is for interpretation really depends on the client and the kind of collaboration they’re open to.

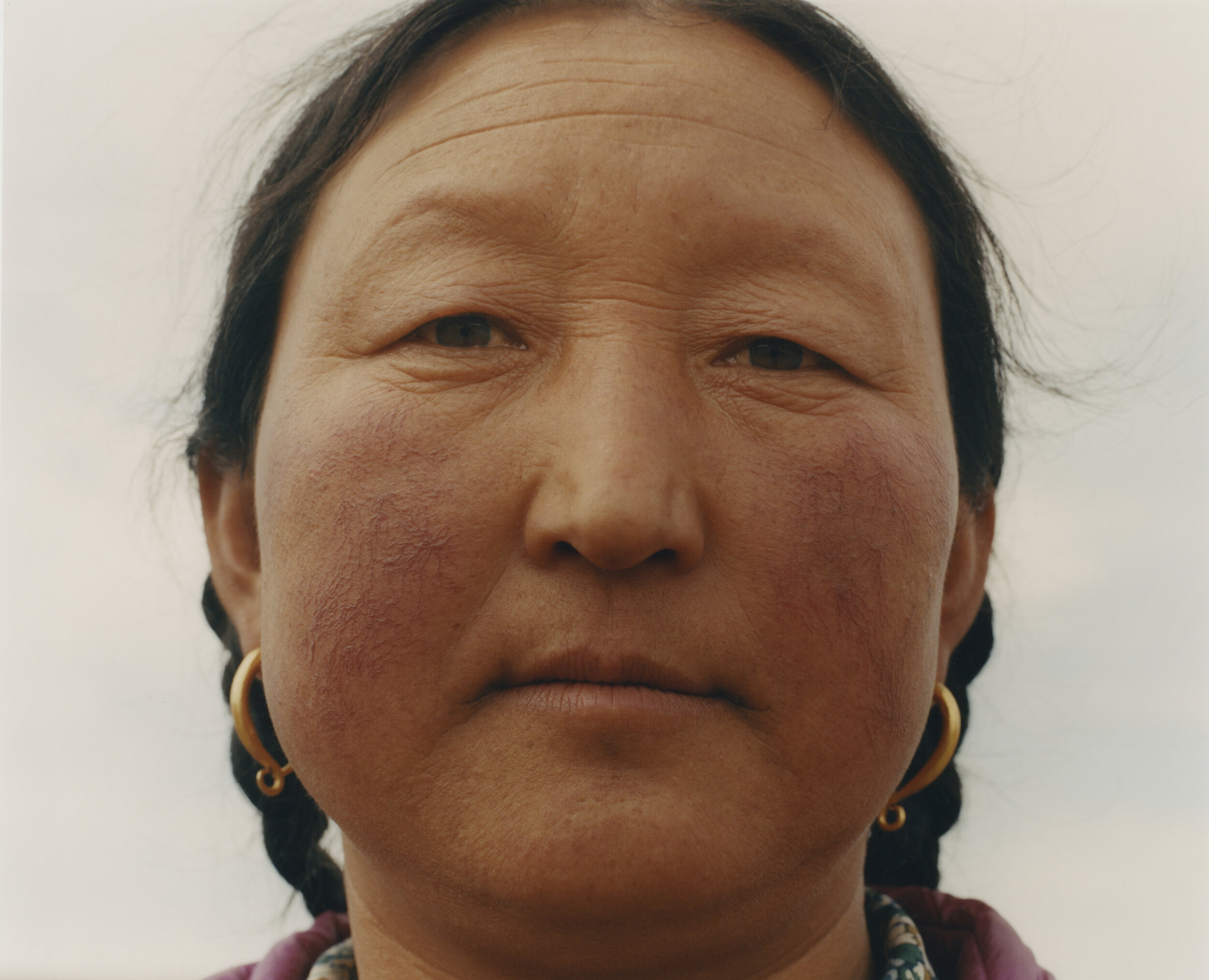

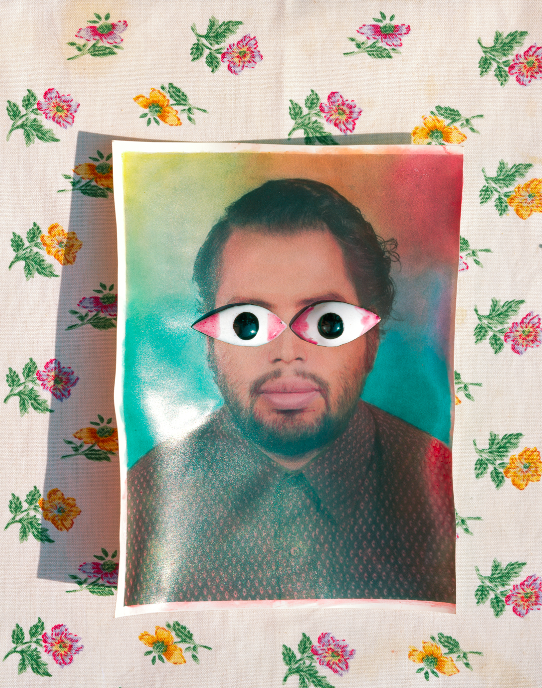

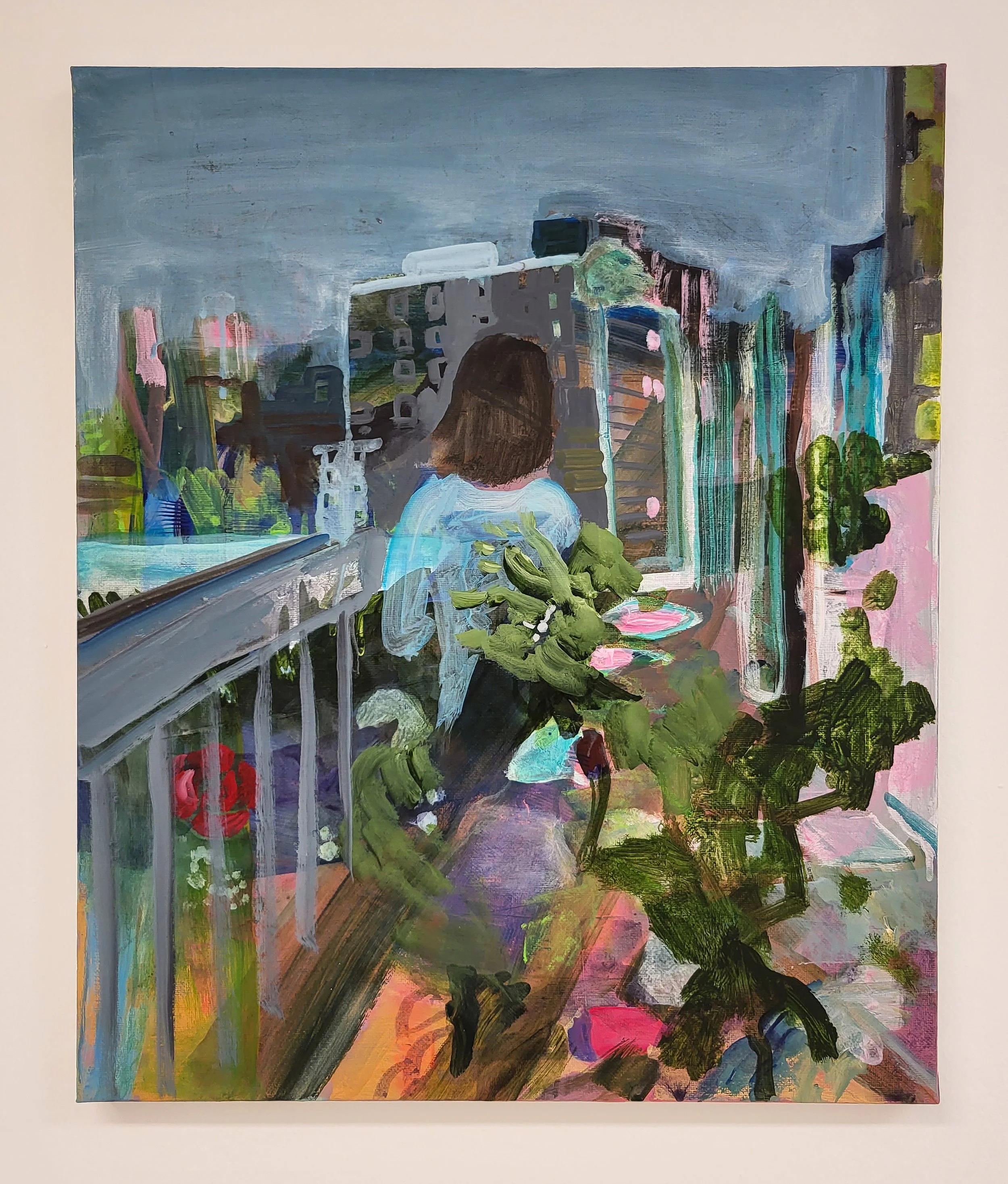

Personal work feels much more open ended. When I’m photographing people for my own projects, I often begin with conversations. Listening, sharing experiences, and allowing the process to unfold slowly. Sometimes the work comes from simply spending time together and experimenting with the camera. Other times, it starts with mood boards, or even just a few sentences I’ve written down to understand what I’m feeling and why I want to make the work.

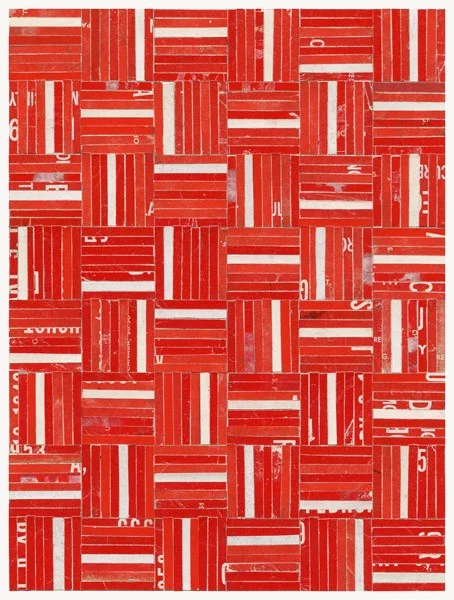

Color is something that comes very intuitively to me. I think growing up in South India, surrounded by strong reds, oranges, and saturated tones in everyday life, has shaped how I see and respond to color. It’s less of a conscious choice and more something that naturally finds its way into the images.

Can you tell me about your relationship with India and how your perspective on its culture has evolved?

For a long time, my relationship with India was complicated. Many of my experiences growing up, both personal and societal, were difficult, and that shaped a sense of distance and frustration. It often felt like a place I needed to push against in order to survive or grow.

As I’ve gotten older, and spent more time moving through different parts of the country, my perspective has shifted. I’ve developed a deeper respect for the culture and its contradictions. India is not an easy place to exist in, especially as a woman, and the political climate adds another layer of complexity to everyday life.

At the same time, these days I find a lot of hope in the people I encounter. Artists, writers, and communities who are speaking openly about what isn’t working, sharing lived experiences, and collectively trying to reshape social norms. Witnessing that honesty and resistance has changed how I relate to the country. It feels less like a place to escape from, and more like a place I’m still learning how to engage with.

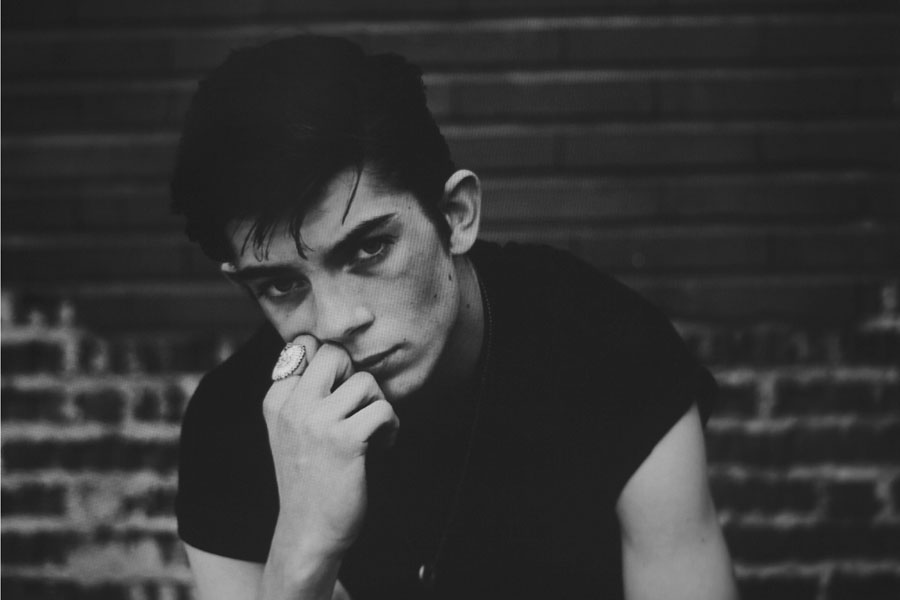

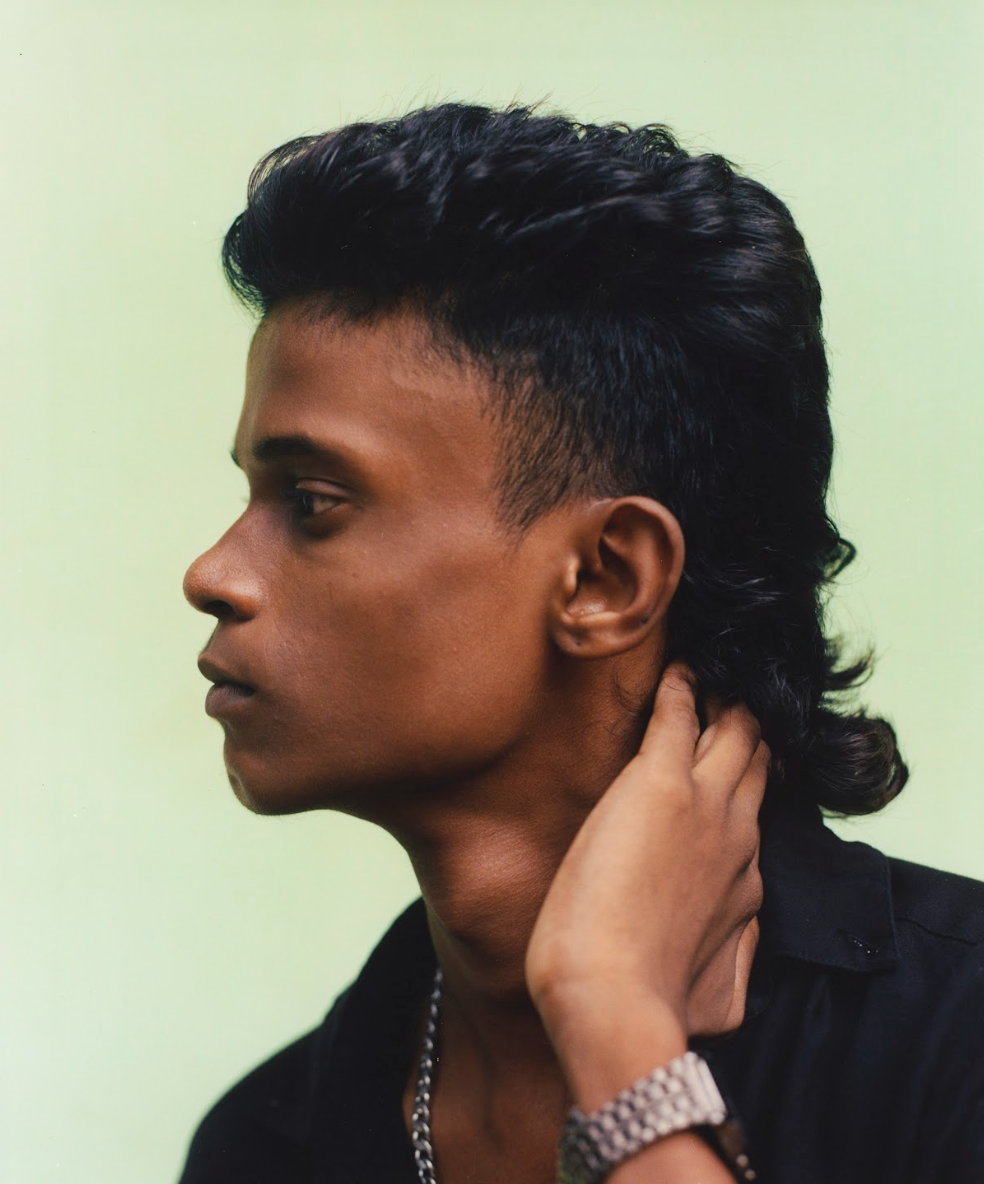

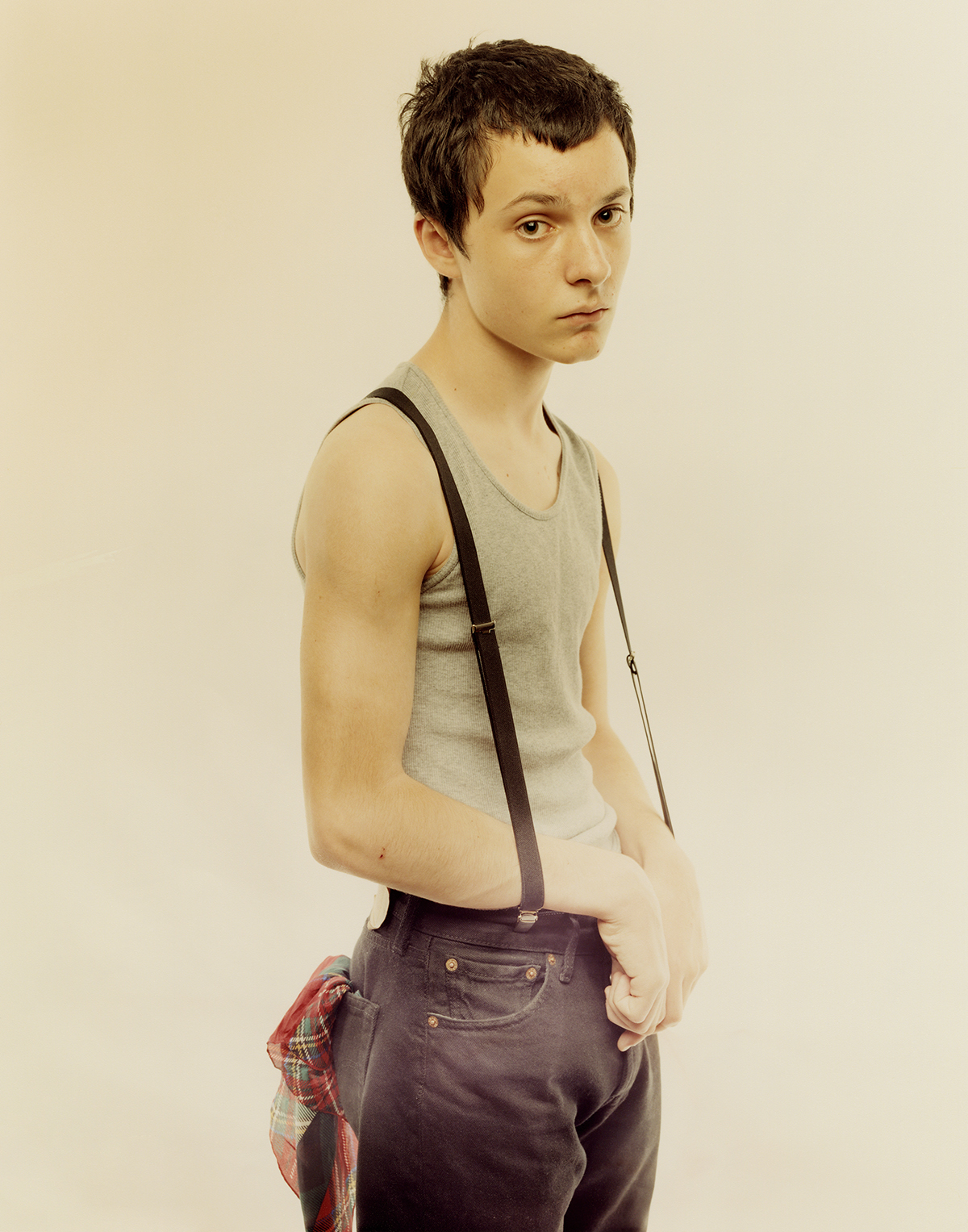

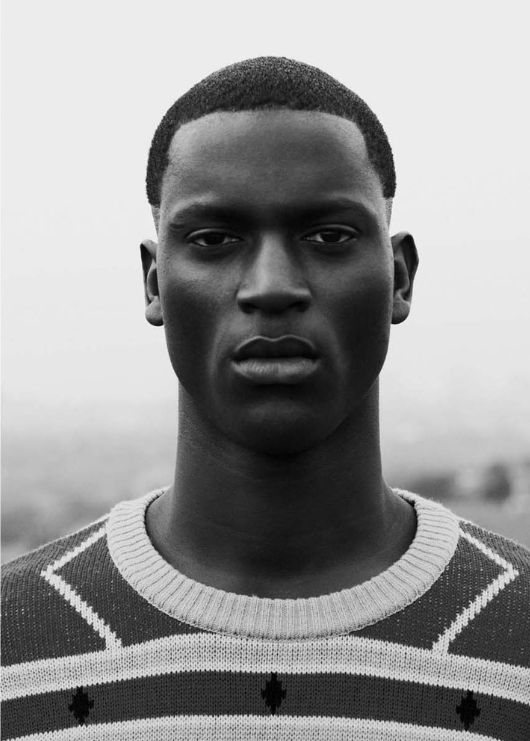

Your portraits convey a lot of strength. Is that intentional?

In some cases, yes it’s very intentional, especially in projects like the bodybuilder series. In other instances, it’s less about directing that quality and more about what naturally comes through from the person themselves. I think a lot of the strength you see is simply translated from the subject. I try to create the space and then let them show up as they are.

What do you want people to take away from your work?

I don’t think I want to be too prescriptive about that. If anything, I hope the work encourages people to pause and look at experiences beyond their own. Maybe it allows them to feel seen, or to recognise something familiar in someone else’s story. And if it creates space for people to reflect, or even feel a little more open to sharing their own experiences, that feels enough.

See more work at https://keerthanakunnath.info/ & @kee_kunnath